First Religious Society Unitarian Church

26 Pleasant Street, Newburyport, MA

Report on Quarried Stones in Foundation

Built in 1800

By

James Gage and Mary Gage

Issued August 30, 2013

Revised December 8, 2013

© 2013

On Sunday August 18th we were given a tour by Bill Heenehan of the interior of the church’s foundation. We were looking for marks left on stones from the quarrying and splitting process. A large portion of exposed bedrock in the cellar now in the main hall was jack hammered to reduce it circa 2000. Old splitting marks, if any existed were lost. The back end of the cellar used to house the new furnace was left in its original 1800 state. Here we found evidence of splitting and a sample of the original interior foundation wall.

The rear end wall was completely exposed. The bedrock ledge was partially exposed and partially covered in loose fine dirt. The ledge took up approximately half the room. The room is walk-in height on one side and crawl-in height above the ledge. The rear wall was built with varying heights across the top of the ledge.

Bedrock Ledge

The exposed ledge was across the rear end and along the northeast corner (off street side). It starts out low on the Unicorn Street side and gains height across the rear end which continues along the off street side. The exposed top edges show hammer marks indicating a heavy hammer was used to break off chunks of stone. There were no drilled holes or half holes known as quarry marks in the upper portion.

The first expense in the account book for the construction of the New Meeting House is dated July 11, 1800 and reads, “To cash p’d liquor for people getting out stones.” (Atkinson, 1933, 44; First Religious Society, n.d.) The liquor was likely for a work party formed to break up the ledge. It was customary to supply liquor at these events especially if all the help was voluntary.

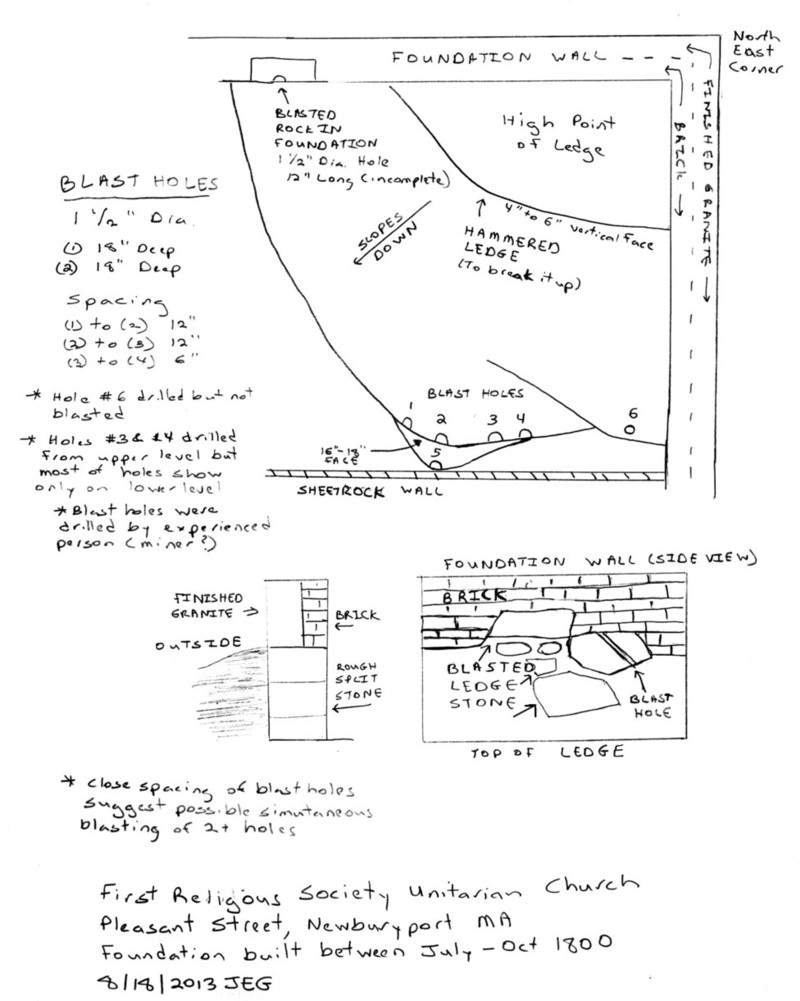

On the lower exposed portion on the off street side next to the wall board forming the meeting hall room there were six 1½” diameter drilled holes. These are the remains of blast holes. The depths varied because a few had the tops blown off from the blast. Several had intact bottoms. Four holes were lined up in a row across the upper level with 12” between holes 1, 2 & 3 and 6” between holes 3 & 4. One hole was found on the lower level. This was up against the wall board. A sixth intact hole was found a few feet away on the upper level where work appears to have halted on the breaking up of the ledge. That hole was drilled but not blasted.

The drilled holes are perfectly round, neat and clean. They were drilled by an experienced man with a sharp drill. That man was likely an ore miner and not a quarryman. The holes are confined to a small area indicating the man was brought in after other men had attempted to break the stone off with hammers as indicated by the upper rear section that does not have drill holes. The upper section was sufficiently low as to not interfere with the building so it was left as is and simply built on top of.

Rear End of Foundation Wall

The bottom of the wall was constructed using large boulders with flat faces. Some of the boulders appear to come from the pieces of stone broken or blasted off the ledge. One boulder contained the remains of a 1½” diameter blast hole confirming that some of the stone used in the construction of the rear end wall came from the blasted bedrock ledge in 1800. The account book for the building of the New Meeting House indicates additional cellar stones were purchased to supplement the stones blasted from the ledge. The exposed interior stonewall has a flat face. The builders chose stones with a flat face or purposely flatten the face of the stones used, making an extra effort to create what is termed a “flat faced” wall. This is usually reserved for the exterior side of walls not interior walls. Most cellar walls are constructed with round faced boulders.

Above the boulders bricks were used on the interior to raise the foundation to the intended height. On the exterior were quarried granite blocks and bars. The bricks and granite were back to back forming the top layer of the foundation.

Exterior Foundation Wall around Perimeter of Church

Granite bars and blocks are the only stone seen on the exterior of the foundation. The granite was shaped into long bars for the walls and blocks for the corners. The exterior of each piece was worked to a flat rough finish. Great care was taken to remove the quarry marks. The intention was to have a finished surface on the exterior.

During the renovation a part of the Unicorn Street side wall of the foundation was removed. A few of the granite bars were preserved and set on the church grounds. They are on the Pleasant Street side forming part of the walkway with a single bar set out on the lawn. These should be labeled for future research purposes. (Sample signage or plaque “These granite bars came from the church foundation built between July and October 1800. They were removed during renovations in [year].”

The bars have three rough sides and one finished side. On a few of the bars the flat-wedge quarry marks are present. No round hole quarry marks were found except on the end of one bar that was shortened to fit in its new place. There is no patina in the half-round holes showing the round holes used to split the bar are modern circa 2000.

The flat-wedge holes are spaced 4” to 5” apart typical of this type of hole. The hole is trapezoid shaped with a wide top and narrow bottom. The original hole was a slot approximately ½” wide by 2” long. A cape chisel was used to create the hole. It was not drilled like the round holes using plug drills. A cape chisel chipped the stone out across a short length in a narrow slot.

The reason the authors are so interested in the quarried granite with quarry marks is the 1800 date pushes back the date of using the flat-wedge method by three years. That may not sound like much but it is an important find. The earlier date now raises the question where (what town) was the stone being quarried? Bill after thinking about it we are inclined to agree with you the stone was not quarried in Quincy. The reason being was the gentlemen who owned a stone quarry in Quincy did not celebrate finding a new method until 1803. (Pattee 1878, 515) The scant historical reports suggest that new method was the flat-wedge method.

Of just as much importance are the blast holes in the ledge. This is the second oldest dated building in New England with blast holes. The other building the Hempsted house in New London, Connecticut dated to 1758 has the only other known early blast hole. It was a rare find.

Circa 1803-04 Lt. Governor Robbins found a building with foundation stones that had unfamiliar quarry holes placed every 6” to 7” in Salem, MA. The spacing indicates the round hole which uses that spacing. Robbins inquired with the owner about the stones who said a Mr. Galusha was the contractor who built cellars. Mr. Galusha said he obtained the stones from a Mr. Tarbox in Danvers, 2 to 3 miles away. The Governor brought Mr. Tarbox to Quincy where he introduced his method to the various stone quarries. Mr. Tarbox’s method reduced the time it took to quarry a block of stone and in turn, reduced the price of quarried stone dramatically. The Governor for several years had wanted to build a stone jail in Charlestown but the cost of quarried stone was too expensive. (Shaw 1859, 357-359) In 1804 the Charlestown jail was started. Sadly, the jail was demolished without an archaeological investigation so it is not known what method was used to quarry the stone.

A well dated house built in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts now owned by the Peabody Essex Museum has similar quarried blocks as found in the church. The granite was quarried using the flat wedge method.

As to the question where did the quarried granite come from that was used in the church? The Quincy quarries were in operation at that time but did not start using the flat-wedge method until 1803. The Rockport quarries did not open up until the early 1820’s. Mr. Tarbox was quarrying stone in Danvers and shipped it by land over to Salem due to the short distance. However, it was more common to ship stone by boat. A March 5, 1803 advertisement in the Columbian Centinel has a listing for the sale of a stone quarry in Little Cambridge noted it was about one mile to a wharf on the Charles River whereby the stone could be shipped to Boston and Charlestown at “very little expense.” This does not get us any closer to figuring out where the quarried granite came from for the church.

We have walked many miles of woodland in the Newbury area. To date we found one small boulder quarry on a farm off of Orchard Street. It is part of the Martin Burns Wildlife Management Area. Boulder quarries produce stone of varying colors and types. That is different from the quarried stone which is all the same color and texture used in the church. The church stone came from a single stone ledge. Furthermore, the men at the boulder quarry used both the round hole and flat-wedge hole. No round holes were found in the church stones which eliminates the Newbury boulder quarry. The lengths of the bars used in the church foundation suggest a surface ledge quarry whereby the lengths could be regulated and there was sufficient quantity of the same type of stone to have a uniform foundation. Examples of surface quarries have been found in Manchester, Massachusetts and Sandown, New Hampshire (beside the old railroad track bed and used by the railroad for culverts) (plus a couple more found on a woodlot not associated with the railroad). Surface quarries are small and easily buried with leaf debris and humus thus their locations are often lost over time. That said, there could be old surface ledge quarries in the Newbury area we do not know about.

Account of expenses incurred with The New Meeting House between the years 1800 & 1801.

Among the expenses were entries related to stone. The amounts are dollars and cents.

1800

July 11 – To Cash p’d liquor for people getting out stones 2.47

July 14 – Sam’l Cutler’s bill 11 Stones 57.25

October 6 – Caleb Abbots bill hauling Stone 15.67

October 8 – J. [Jacob] Galusia’s bill Stones 289.16

These entries are vague but valuable. The first entry was for cash paid for liquor to a work party. The top of the ledge has evidence of hammering to break apart the stone into movable and useable pieces. It suggests a group of church members attempted to break up the ledge to get cellar stones. Part of the process of breaking up the stone was done by drilling holes and blasting the ledge. This was done in a small tight area. There were six blast holes of which five show evidence of blasting, one is still intact. There are numerous entries for labor but none appear to be associated with a person blasting. This person may have been a member of the church who offered his services along with the general party of men attempting to break up the ledge with hammers. The small exposed area in the back section although limited in scope has only one small area with blast holes. It suggests the ledge could not be easily broken up by the then current blasting methods being used in ore mines. However, the blasting was partially successful as seen by the split boulder in the cellar wall with half of a blast hole.

However, it appears that the stone from blasted ledge did not provide sufficient material for the construction of the foundation walls. On July 11 Samuel Cutler was paid for “11 stones.” (Samuel Cutler was a prominent Newburyport merchant who sold a wide range of products.) The July date suggests it was associated with cellar stone. What quantity the “11 stones” refers to is unknown. The 11 may refer to 11 perches or 11 loads of cellar stone. Cellar stone was sold by both units of measure. A perch is a “A unit of cubic measure used in stonework, usually 16.5 feet (one rod) by one foot by 1.5 feet, or 0.70 cubic meter [24 ¾ cubic feet]” (The American Heritage Dictionary). The size of the load dependent upon the size of the cart or wagon.

In 1790, an advertisement offered for sale cellar stones from 3s 6d. [$0.94] to 9s [$2.25] per perched. (Massachusetts Centinel May 5, 1790). In 1836, the prices hadn’t changed much for cellar stone. The American Builder’s General Price Bookand Estimator listed prices ranging from $1.25 to $2.50 per perch. If Cutler was selling by the perch then the price was $5.20 over twice the going rate. Even allowing for a $15 delivery charge, the price would still be excessive at $3.84. It is possible the 11 refers to a wagon load contain more than a perch.

The last two stone related entries occur in October and within two days of each other. The third entry was for a bill for hauling stone. The fourth entry was a bill for the stones. The high price of the stone indicates the bill was for the finished granite used in the foundation. The 4th entry had the name J. [Jacob] Galusia. This is the same stone contractor that Lt. Governor Robbins met in Salem in 1803. Jacob spelled his name Galeucia but it is also spelled Galusha / Galusia / Galucia in various records. (See appendix for more details)

The third entry shows the stones were hauled to the site. This suggests Mr. Galusia purchased the stones from a local stone quarry. It was likely in the Newbury or Rowley area given that Galusia purchased stone from a local quarry (2 to 3 miles away) for his Salem building project in 1803. The quarry’s owner/name and location are lost.

The church’s foundation was completed in late October. This was confirmed by a newspaper article in the Newburyport Herald dated October 28, 1800 announcing the frame of the church had been completed. Between the large sum of money and the October stone delivery it suggests this load of stone was the hammered exterior finish stone. Hammered stone was a common term in the industry. It is found on most old advertisements from stone-cutters. A March 5, 1772 advertisement in the Massachusetts Spy explained the term hammered, “Wanted for building a new MEETING HOUSE, in Brattle Street, Boston, the following Materials, viz. Good Stones for the foundation and cellar, Stones for two or three courses above ground, to be hammered to a good face, each one foot in height, and not less to go into the wall.” The advertisement makes a distinction between “cellar stones” and “hammered stones.”The Unitarian Church had irregular cellar stones topped with several layers of brick on the interior, and two to three layers of hammered stone with a “good face” on the exterior. The foundations of each meeting house utilized the same two types of stones suggesting it was common type of foundation.

Research Purposes

The account record was invaluable confirming an exact building date for the foundation. The hammered stone bars with the flat-wedge marks, pushes that method back to 1800. This is the earliest use of the flat-wedge method at this point and it was in the Newburyport area. That is subject to change if earlier buildings with the flat-wedge method are found.

The clean, neatly drilled blast holes show well developed stone drills were in existence to drill round holes in hard granite. The arrangement of blast holes gives us some insight into ore mine blasting techniques. Overall this new information adds to our knowledge of quarrying, mining and working stone.

Foundation of Previous Unitarian Meeting House

Minnie Atkinson noted in her book on the First Religious Society that the church salvaged the cellar stones and underpinning of the old meeting house. (Atkinson 1933, 42) Did they reuse those stones in the new meeting house? The old meeting continued to be used until a week before the new meeting house was opened for religious services. Therefore, the cellar stones and underpinning were not salvaged until after the new meeting house was completed. The Society would have sold these salvaged building materials to help offset the costs of the new building.

Section of the ledge broken up by the use of sledge hammers

Stone in rear foundation wall with 1 ½” diameter blast hole

Blast holes in the ledge

Close-up view of blast hole

Flat wedge quarry marks on stone taken from foundation. The marks are on a side of the stone that did not show. The opposite side of the stone had a smooth finish (see next photo.)

Finished surface of the granite stones used on the outside of the foundation where it showed above ground. This finish was known as “hammered stone.”

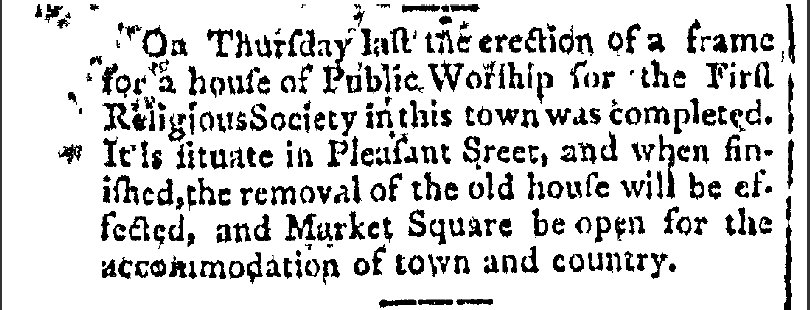

Newburyport Herald October 28, 1800

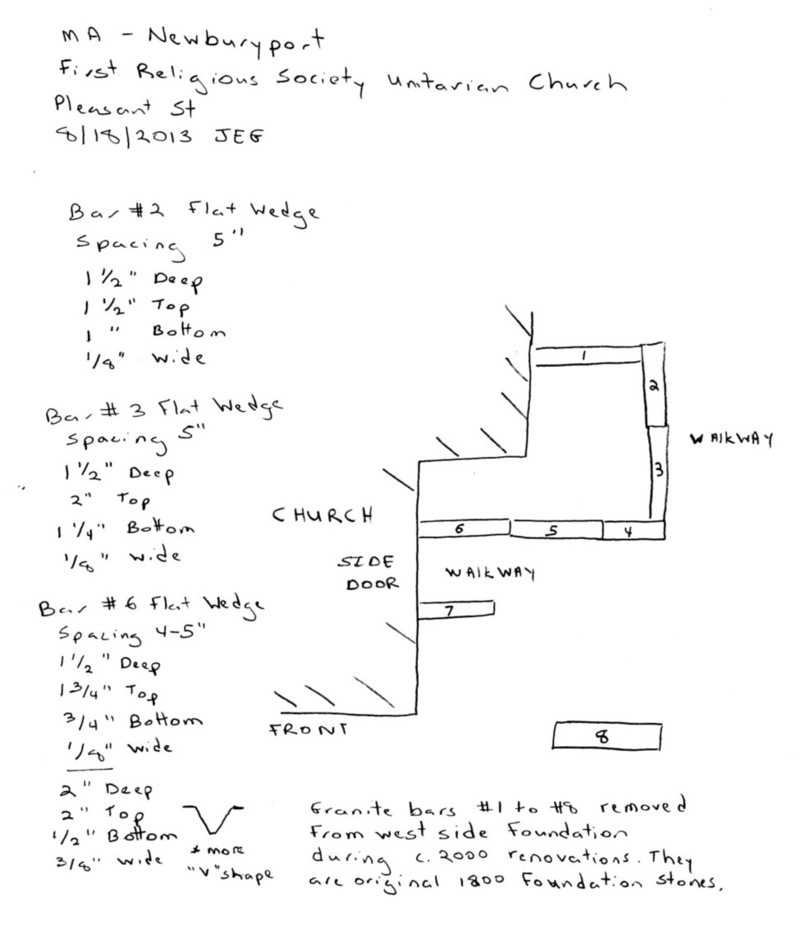

August 18, 2013 Field Notes

August 18, 2013 Field Notes

APPENDIX

Stone Quarries: 1803 -1805

Tyngsboro Quarry “Hammered Stone”

Newspaper: Wednesday, April 3, 1805, Independent Chronicle (Boston, MA)

Sheffield, MA “variety of Marbles” mainly for smaller sculptured items like urns and busts – Newspaper: Wednesday, September 11, 1805, Democrat (Boston, MA)

Little Cambridge, MA “Stone Quarry” advertisement for the sale of the quarry which had “excellent Building STONE”. It was noted, “stones may be brought to Boston or Charlestown with very little expense”

Newspaper: Saturday, March 5, 1803, Columbian Centinel (Boston, MA)

Quincy stone quarries are known of by the 1803 celebration by the owners of a Quincy quarry and Lt. Gov. Robbins bringing Mr. Tarbox out to the quarries in Quincy circa 1803-4. (Pattee 1878, 515)

Braintree & Quincy quarries were mentioned in the 1805 Tyngsboro advertisement comparing the northshore stone to that found on the southshore.

Danvers, MA via Mr. Tarbox supplying Mr. Galusha stone for a building in Salem. (Shaw 1859, 357-359)

Stone Dealers: 1790 - 1805

Several newspaper advertisements were found for stone dealers selling: cellar stones, well stones, hammered stones and other types of stone at wharfs in the Boston area. The stone merchants purchased numerous different types of stone from quarries but did not state their sources.

Jacob Galeucia [Galusia / Galusha], Stonecutter

Surname had several spellings: Galusha, Galeucia, Galucia, Galusia

Jacob was listed as a stonecutter at his death on April 10, 1849 at age 74 (“Massachusetts, Deaths, 1841-1915” FamilySearch.org)

He was born Feb. 10, 1775 in either Danvers or Salem, conflicting towns listed on different sources

He married Sally Newhall in Danvers on April 12, 1794 (Danvers Vital Records)

His name, J. Galusia was listed on a bill for stone for the New Meeting House dated October 8, 1800

The owner of the Salem building circa 1803/4 told Lt. Gov. Robbins, Gulasha was the contractor. Gulasha told Lt. Gov. Robbins he purchased the stones from Mr. Tarbox indicating he was responsible for building the foundation but did not quarry the stone himself. This is confirmed by his occupation at his death as stonecutter. Stonecutters dealt with finish work (see Stone Types below)

Jacob Galusia lived in Danvers all his life. He worked up and down the coast as evidenced by the Salem building and Newburyport’s Unitarian Meeting House. He was a stonecutter. He did not advertise. Judging by the fact he was hired in Newburyport he was well known on the coast. He was twenty-five years old in 1800 when he was contracted to do the finish /exterior stonework on the church’s foundation.

Stone Types

The following list comes from a public notice in the May 1, 1799 Columbian Centinel (Boston, MA). It was an advertisement for submissions for a building contract for the Alms House.

“400 perch of good cellar stone, consisting of quarry and sl[a]te …

as will accommodate the Masons

[Perch: “A unit of cubic measure used in stonework, usually 16.5 feet (one rod) by one foot by 1.5 feet, or 0.70 cubic meter [24 3/4 cubic feet]” - The American Heritage Dictionary]

600 feet running measure of hammered stone, 15 inches high

1900 feet running measure white stone for facia … the stone-cutters to assist in laying them.”

There were three different stone types: cellar stone, hammered stone and white stone. The cellar stone was purchased by the perch, a specific quantity. The cellar stones were listed as “quarry” and “slate”. What does the term quarry indicate? It was paired with slate. Slate was a specific type of stone. This suggests quarry was an early term for granite. Slate is best known for it use in gravestones, and shingles to cover the outside of buildings and roofs. The advertisement for the Alms House building contract shows slate was also used for cellar stone.

The hammered stone was purchased by the “running measure” which is interpreted as sold by the length. This was confirmed by another advertisement where hammered stone was sold for 1s to 1s.6 per foot (Massachusetts Centinel, May 1, 1790, Boston). An earlier 1772 advertisement, “Wanted for building a new MEETING HOUSE, in Brattle Street, Boston, the following Materials, viz. Good Stones for the foundation and cellar, Stones for two or three courses above ground, to be hammered to a good face, each one foot in height,” The height of 12 inches and 15 inches indicates these were bars of stone. The 1772 says, “to be hammered to a good face” indicating at least one face of the bar was to be have a flat face which is found on the exterior side of above ground stone bars in many foundations. The name “hammered” was associated with bars of stone with a finished face for the above ground exterior of foundations.

The white stone for the “facia” was for stone with a finished face for the exterior face of the building. This was confirmed by a professional drawing of the Boston Alms House built between1799-1801. The Alms House was designed by Charles Bullfinch who favored the use of a white granite known as “Chelmsford Granite.” This is likely the white stone referred to in the advertisement.

The white facia stone on the exterior covered a brick building. This is noted by “From 10 [1,000,000] to 1200,000

[1,200,000] good merchantable well-burnt bricks, to be delivered to the spot.”

The advertisement distinguishes between different types of workman dealing with stones. The men building the cellar were (stone) masons. They were responsible for the thick support wall under the building. The men working with the white facia (exterior finish) stone were stone-cutters. They were responsible for the preparing stones used on the façade of the building. Although not masons they were there to assist in the laying of the exterior stone. Stonecutters were men who took rough cut stone and worked the stone’s surface to a fine finish. Each denotes a different trade.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Atkinson, Minnie

1933 A History of the First Religious Society in Newburyport, Massachusetts.

First Religious Society

n.d. The New Meeting-House [account] Newburyport Public Library Archival Center, MS N974.4512 U58 Carton 1, Folder “1800 New Meeting House.”

Gage, Mary & James Gage

2005 The Art of Splitting Stone: Early Rock Quarrying Methods in Pre-Industrial New England 1630-1825.

Amesbury, MA: Powwow River Books.

Gallier, James

1836 The American Builder’s General Price Book and Estimator. 2nd Ed. Boston: M. Burns.

Pattee, William S.

1878 A History of Old Braintree andQuincy. Quincy, [MA]: Green & Prescott.

Shaw, Lemuel

1859 Proceedings of the AmericanAcademy of Arts and Sciences. Boston, MA: The Academy.