Saint Aspinquid’s Cairn & Mount Agamenticus

By Mary Gage and James Gage

Independent researchers, jgage@nesl.edu

© 2021-2022. All Rights Reserved.

Revised 11-22-2022

Introduction

Since the late 19th century, a stone cairn on the summit of Mount Agamenticus in York, Maine was considered the burial place of Saint Aspinquid, a Penobscot Mi’kmaq tribal leader converted to Christianity by the Jesuits in the late 1600s. An elaborate and highly embellished legend about St. Aspinquid was first published in 1768 in the Halifax Gazette (Nova Scotia). It was quickly picked up and reprinted by the Boston News-Letter in Massachusetts. The legend resurfaces decades later in 1818 and became wildly popular throughout the 19th century. Interest in the legend has remained unabated up to the present day. The story has been largely dismissed as fictional but both the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia and local Native Americans in the York, Maine area consider St. Aspinquid’s burial place to be real and culturally important to them. Is there any factual truth behind the legend?

Aspinquid and three other tribal leaders were murdered by colonial soldiers in 1696 at Fort Pemaquid in Maine during a peace conference. Sixty years after his murder, people in Nova Scotia celebrated a feast day for St. Aspinquid and made annual pilgrimages down the coast to Mount Agamenticus to his grave. These pilgrimages suggest there is some truth behind the legend.

By the late 1800s, a stone cairn on the summit of the mountain had become associated with his grave site. However, recent research has shown that the summit cairn was built by the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey in 1847. A fact which became lost in subsequent decades after its creation.

If the summit cairn is not St. Aspinquid’s grave then where is it? Since the mid-1700s all the focus has been on St. Aspinquid. The three other tribal leaders who were also murdered with him have largely been forgotten. The prevailing assumption has been a single grave rather than four graves.

A walk deep in the woods turned up a large cairn next to four graves! Could this be the burial site of St. Aspinquid and his companions? Was there originally a memorial cairn associated with the graves? (Figures 1 & 2) The answer to these questions is complicated. This was likely the place the pilgrimages went to but the “graves” were memorials rather than burials. (The actual burial location on the mountain remains unknown.)

|

Figure 1 – Four pseudo (memorial) “graves” numbered and outlined with surveyors tape in the field.

Figure 2 – Close-up one of the four graves

Memorial Cairns

Did Native Americans in New England build memorial cairns?

Woodbury, Connecticut

Writing in 1872 William Cothren author of History of Ancient Woodbury, Connecticut from the First Indian Deed in 1659 to 1872, relates an old Native American custom, “The Indians had a very beautiful custom of honoring their dead chiefs, when laid in their last repose. As each Indian, whether he was on his hunting expedition or the war-path passed the grave of his honored chief, he reverently cast thereon a small stone, selected for that purpose, in token of his respect and remembrance. At the first settlement of the town [1672], a large heap of stones had accumulated in this way, and a considerable quantity yet remain, after the tillage of the field in its vicinity for the long period of two hundred years. These stones, thus accumulated, were of many different varieties, a large number of them not to be found in this valley, nor within long distances, showing clearly that there was a purpose in their accumulation and verifying the ‘tradition of the elders,’ that they were gathered there as a monument of respect and honor to a buried chieftain.”

Cothren as an astute historian verified the oral tradition by vetting it against what he encountered in the field, the remains of a large stone mound.

Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts

According to anthropologist Frank Speck, “Southern Massachusetts also has a memorial marker in the stone-heap category. On the main highway between Edgartown and Chilmark, on the Island of Martha’s Vineyard is a small pile of round cobblestones appropriately marked by a tablet enclosed with a fence – a conspicuous archaeo-historical site for the tourist. It marks the spot where missionary Thomas Mayhew, Jr. who converted the tribes on Martha’s Vineyard, bid farewell to the company of natives who accompanied him this far from their village when he took his departure for England in 1657. It was on this voyage that he was lost. Says the historian Banks, ‘No Indian passed by it without casting a stone into the heap, that by their custom had grown like a cairn.’ ”

Speck’s account acknowledges there had been a memorial stone mound erected by the Native Americans beginning circa 1657 to their beloved preacher Thomas Mayhew, Jr. Although it appears Speck questions if the small cairn is original.

These two accounts show memorial stone mounds were used in the 1600s.

Mount Agamenticus and St. Aspinquid

Thy hoary peaks bear the names of chiefs and heroes who are not myths, and in the hearts of the people they are an everlasting memory.Fred Myron Colby (1885)

Timeline

St. Aspinquid (Silent Net) whose name has numerous different spellings was a Penobscot Mi’kmaq sachem from the Penobscot Bay area of Maine. According to Mi’kmaq oral history he was a holy man and prophet. He is credited with bringing many Native American women and children from New England to safety in Nova Scotia. This timeline highlights some of the key events in his life and the subsequent legend that emerged after his murder in 1696.

1689-1694 At some point during this time frame, Aspinquid had a vision on Mount Agmenticus according to Mi’kmaq oral tradition. As a result of the vision, Aspinquid converted to Catholicism and devoted himself to humanitarian efforts to protect his people.

1693 – A Peace Treaty was signed at Pemaquid, Maine by Aspinquid, Edgeremett and about a dozen other Native American sachems from different tribes.

1696 – Aspinquid was part of a Native American delegation that traveled to Fort Pemaquid in Maine to discuss a prisoner exchange. During the diplomatic negotiations, Captain Chubb, commander of the fort and a number of colonial soldiers, attacked the delegation murdering Aspinquid, Edgermett and two other Native Americans (Wipenen, son of Edgermett, and Peminuit) under a flag of truce. Assacumbuit was captured, placed in chains and imprisoned until freed months later when the French captured the fort. Moxus, Mejilapeka’tasiek, and Francis Algomatin escaped the ambushed.

Pre-1749 According to historian Don Awalt (Mi’kmaw), “The Feast of St. Aspinquid (The Old Spring Feast) predated the arrival of the Europeans and was the great social event of the year in the Mi’kmaq community. Clans would descend on Chebucto’s Northwest Arm from as far away as the Mirimachi in New Brunswick and the Penobscot in Maine. With the arrival of the English settlers, the founding of Halifax (1749), and the ensuing hostilities, the feast was put on hold for a decade.”

1768 - 1786 The celebration of St. Aspinquid Day in Halifax, Nova Scotia has been traced back to 1768 in published accounts as noted by intermittent references in newspapers and almanacs. The 1768 date agrees with Awalt’s account that St. Aspinquid’s Feast Day was revived around the 1760s.

On June 30, 1768 the Boston News-Letter (Boston, MA) reprinted an article from the Halifax Gazette (May 12th issue). It begins “As some of your Readers may be ignorant of the Day of the Festival of Saint Aspinqiud” and goes on to tell a very elaborate tale about this saint. It includes a family genealogy declaring St. Aspinquid was descended from the lost tribes of Israel who migrated to North America via the Bering land bridge. It states authoritatively that “Some Years past in my [Mr. Ames] Travels through the Eastern Parts of New England, I Passed thro’ Several Tribes of the Aborigenes, and in particular the Norridge-walks [Norridgewock Tribe of Maine], where I met with one Bomazine [Bomazeen] their Chief Sachem, who kindly invited me to examine their Archives, where were deposited a Number of valuable Manuscripts, among which I found the Life of St. ASPINQUID, (the only Person who has ever been sainted in New England) …” The article concludes with a description of St. Aspinquid’s funeral “…for after a Life of Ninety four Years Fifty thereof were signalized by the most benencent Acts, he expired in Mount Agamenticus, the 1st May 1682, where his Sepu’chre remains unto this Day, and on his Tomb-Stone is still to be seen in this Couplet :

Present useful, absent wanted,

Liv’d desir’d, died lamented ;

The Sachems of the different Tribes attended his funeral Oblequies, and made a Collection of a great Number of Wild Beasts to do him honor by a Sacrifice on this Occasion, according to the Custom of those Nations, and on that Day were accordingly Slain, 45 Bucks, 67 Does, 99 Bears, 36 Moose, 240 Wolves, 82 Wild-Cats, 3 Catemounts, 482 Foxes, 32 Buffaloes, 400 Otters, 620 Beavers, 1500 Minks, 110 Ferrits, 520 Raccoons, 920 Musquash [muskrat], 501 Fishes, 1 Ermine, 38 Porcupines, 50 Weasels, 832 Martins, 59 Wood-Chucks, and 112 Rattle-Snakes.” Buffalo are not found in the northeastern United States. This is an embellished account of the feast but it made for exciting reading material. This story seems to have influenced the festival held in Halifax in the 1770s. Wild game was served but not in those quantities or diversity. A 1773 account of the festival listed “bear and venison hams, moose tongue and various fish.” The inscription on the tombstone mentioned in the article comes from a 1719 epitaph written by a Rev. Danforth in Dorchester, Massachusetts.

1773 – St. Aspinquid’s Day was accompanied by an annual pilgrimage from Nova Scotia down the coast to the grave of St. Aspinquid on Mt. Agamenticus in York, Maine. An anonymous writer mentioned the event in a letter he wrote to the editor of the Nova Scotia Gazette in 1773: “… I advise that next year they join the pious company who perform the annual pilgrimage to visit the tomb of our saint on Mount Agamenticus …” Who the group consisted of is unknown: Euro-Americans? Native Americans? Mixed? The pilgrimages confirm one crucial fact: St. Aspinquid’s grave or pseudo grave on Mount Agamenticus existed in the 1770s. Unfortunately, the exact location of the grave is not mentioned. There is no reference to a cairn either.

1786 – This is the last year St. Aspinquid Feast Day was held. From then on it was never revived.

1818, 1824, 1832, 1833 – A slightly modified version of the St. Aspinquid’s funeral from the 1768 article resurfaced decades later in 1818. The legend became popular and was republished in numerous newspapers and books in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. This came during the early stages of tourist travel.

1837 – Some the earliest tourist accounts about the mountain start to show up in newspapers and journals (magazines). The tourists combined a trip to see the great views from open summit with efforts to search for St. Aspinquid’s grave.

1847 – The U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey built a cairn on top of the mountain as part of a triangulation survey.

1857 – A local tour guide took a reporter up the mountain. On their way back down the mountain the guide stopped to tell the tourists a couple of stories. The reporter wrote, “… we emerged from the forest to the open plain. Proceeding along a path our guide pointed to a pile of stones saying – ‘There’s a pretty monument, isn’t it?’ We looked at the cairn, some twelve feet high, a rod [16 ½ feet] or so long and perhaps a rod deep … ‘That’s his [Thimbleberry’s] grave over there.’ He pointed as he spoke to a rough frame, a few rods to the eastward of the monument, where the old cuss reposed …”

Thimbleberry is not a surname in any genealogy database. It is a native plant similar to Red Raspberry with no thorns. Its name comes from its thimble like shape.

The pseudo grave was likely surrounded by a wooden fence as indicated by a “rough frame” next to a large stone pile. The grave and cairn were in an old pasture “open plain” near the base of the mountain as in a short distance they reached the stable where the horse and wagon was left. The story was a tall tale contrived to entertain tourists. The guide had no idea of who was buried there as he does not mention St. Aspinquid or the legend. However, in due time, the locals figured out how to exploit the legend.

1870s – A local family, the Traftons, took advantage of the tourist trade. They offered paid wagon rides up the mountain along with a guided tour. Tall tales are always exciting. Piles of stones seen in route up the mountain were called “the field of ‘Indian graves’.” This is the first printed account that associated stone piles with the Native Americans. It likely contributed to an assumption the cairn on top of the mountain was St. Aspinquid’s grave site.

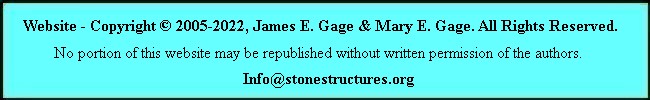

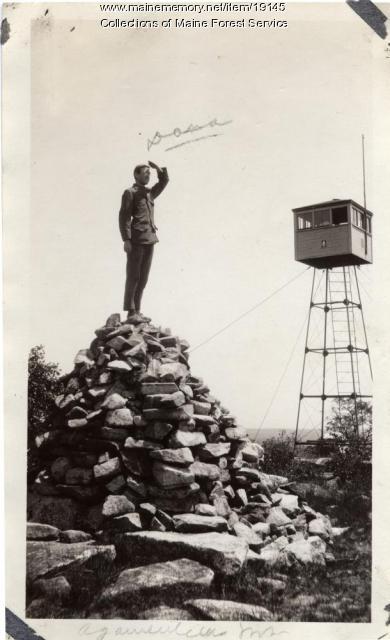

1875 – Author and historian Samuel A. Drake is the first to mention the presence of a cairn on the summit. An 1877 article in the Portsmouth Journal (October 10, 1877) attributed the cairn’s construction to the U.S. Coast [and Geodetic] Survey when they used the summit as a triangulation station in 1847. The cairn was used as an observation point. A USGS survey report in 1894 described the cairn as fifteen feet high by eight feet square. A circa 1920 photograph with a ranger on top shows an approximately twelve feet high by eight feet wide (four sided) semi-cone shaped cairn. (figure 3) A 1922 photo in Sprague’s History (figure 4) under an article by J.H. Shaw shows a similar cairn although that cairn appears to have more of a dome shape possibly due to the low position of the photographer.

1882 – The 200th Anniversary of St. Aspinquid’s death was celebrated on top of Mt. Agamenticus based upon the legend which gave his death date as 1682 rather than the correct date of 1696. The celebration was held at the summit cairn which was thought to be St. Aspinquid’s grave. The festivities were attended by many people including a nine year old child, named Justin Henry Shaw. [see 1923 below]

1883 – An anonymous contributor to “The Wheelman”, a bicycle magazine, described a tour he made in Maine that included a trip up Mt. Agamenticus. He too went looking on top of the mountain for St. Aspinquid’s grave with the epitaph. He came away thinking a large glacial boulder on the summit was the burial location even though it did not contain the epitaph. He did not equate the USGS cairn with the grave. Everyone was looking on top of the mountain for the grave.

Included in the article was a drawing of a tall column-like cairn. Measurements given in the 1894 Geological Survey of the summit USGS cairn “A rock cairn 8 feet square, 15 feet high…” suggest it is the same structure. The drawing appears to be an artist rendition rather than an on site drawing. (see above 1875)

1899 – A brief article with the title “An Indian Saint’s Tomb” appeared in a syndicated supplement widely circulated in United States newspapers. St. Aspinquid’s grave was described as being “on top of Mount Agamenticus” and “covered with a number of stones.” The article was accompanied by a drawing of a stone cairn with a wooden cross on top that gives a clear but deceiving image. (Figure 5) By this point the association of the grave with the USGS cairn had become deeply entrenched in the popular mythology. (The authors were not able to trace the origins of this article.)

1907 – The Bureau of American Ethnology published a short biography on St. Aspinquid. They went on a fact finding mission trying to avoid misinformation. All their sources could be relocated with the exception of one, the most important piece of information to date: “He [St. Aspinquid] is said to be buried on the slope of Mt. Agamenticus.” (italics are authors’ emphasis)

1923 – Justin Henry Shaw went on to write “Agamenticus Majestic” in which he recounts his visit to the mountain for the 200th celebration of St. Aspinquid. By then the theory that St. Aspinquid was buried under the USGS cairn was well entrenched and considered a fact.

1930 – Mi’kmaq Thomas Meuse, John Raymond, and James Meuse of Nova Scotia made a pilgrimage to Mt. Agamenticus circa 1930. Each carried a stone from home to place on St. Aspinquid’s grave. On the summit they found a cairn which seemed consistent with tribal oral tradition.

1941 or 1942 – The cairn on the summit was destroyed when the U.S. Army built a radar base on top of the mountain.

1965 – A new cairn was built on the summit by the ski resort as a tourist attraction. It was close to but about fifty feet away from the original location of the USGS cairn. The ski resort added a white sign explaining the legend of St. Aspinquid’s grave.

1974 – Mi’kmaq Don Awalt and Belinda Goodman Paul of Nova Scotia likewise traveled down to Mt. Agamenticus bringing a stone to place on the cairn. Unbeknown to them they placed their stones on a newly built and relocated cairn that they thought was the grave of St. Aspinquid.

1980 – Two hundred acres on top of Mt. Agamentiucs was purchased by the Town of York.

2009 – In a controversial decision, the Town of York decided to remove the summit cairn which had grown quite large. The decision was met with substantial opposition from the local Native American community. The town eventually compromised by downsizing and relocating the cairn along with providing a new interpretative sign.

In downsizing and relocating the cairn, the town’s intentions appeared to have been to create an “archaeo-historical site for the tourist.” However, for the local Native Americans it continues to be a place of cultural and spiritual importance. They still place stone prayer offerings on it.

2015 – In this year a large cairn and four graves were discovered deep in the woods by an anonymous researcher.

2017 - Brian Michaud (Mi’kmaq and Pennacook) asked the authors to look at what he thought were man-made stone structures on the summit of Mt. Agamenticus. Brian for many years has been searching for the history behind the oral tradition about St. Aspinquid. In recent years he was instrumental in saving a small portion of the large cairn on the summit thought to be the burial cairn.

Michaud pointed out two areas on the slopes of the mountain where stone piles were located which the authors found and identified as Native American ceremonial stone landscapes (CSL). [Please see Appendix A for an explanation of what a CSL is]. These may be the stone piles the Traftons called “Indian graves.” Afterwards, the authors went in search of the large cairn and graves located on another part of the mountain which had been reported in 2015. We were able to confirm four graves and a large ceremonial cairn.

|

Figure 3 – photo of ranger standing on USGS cairn (Courtesy of Maine Forest Service, https://www.mainememory.net/artifact/19145)

Figure 4 – 1922 photo of the summit cairn which appeared in Spragues Journal v.11 no.2 (1923)

Figure 5 – Romanticized drawing of St. Aspinquid’s grave that was widely circulated in a 1899 newspaper supplement.

Relocating St. Aspinquid’s Grave and Memorial Cairn

Given that the summit cairn was built in 1847 as a utilitarian survey marker, the question becomes where is the actual grave of St. Aspinquid? Is it even on the mountain? Is it even real or is it a legend? How does the stone cairn factor into the story? None of the 1700s sources mention a cairn in connection with the grave. In fact the earliest confirmable association of the grave with a cairn doesn’t occur until 1882. How do all the puzzle pieces of Euro-American historical accounts and Native American oral history fit together?

The 1773 letter to editor in the Nova Scotia Gazette described “… annual pilgrimage to visit tomb of our saint on Mount Agamenticus.” It confirms St. Aspinquid was buried on the mountain but does not give the grave’s location. These pilgrimages likely stopped after 1786 when St. Aspinquid’s Day celebrations were cancelled.

In the 2000s Don Awalt interviewed Mi’kmaq elders who gave a more detailed account of the Ft. Pemaquid murders than the Euro-American accounts. It provided the names of all four men who were murdered. Unfortunately, the Mi’kmaq oral history did not include what happened afterwards with the bodies of the four dead men. That left a key piece of information missing.

In the 1930s, the Mi’kmaq carried on an old tradition of carrying a stone from home (Nova Scotia) to place on St. Aspinquid’s burial or memorial cairn. The placing of stones on the grave of a deceased tribal member who died far from home was an ancient tribal practice (see Mi’kmaq Burials below.) This tradition was continued as late as the 1970s.

Had there been a cairn that went with the burial? Likely yes given that stones were carried from Nova Scotia to add to it. Being a hundred twenty-five years after the cancellation of St. Aspinquid’s Feast Day, knowledge of the old cairn and the custom of a stone offering was likely still known amongst some Mi’kmaq. However, there was an apparent small gap in their knowledge, the exact location of the grave. What they found when they arrived at Mt. Agamenticus was a substantial cairn on the summit which seemed to fit with tribal tradition. By this point, the local population had come to associate the summit cairn with St. Aspinquid’s grave as well. This only compounded the process of cultural transference of the original grave to the cairn on the summit cairn.

Would the Nova Scotians have participated during their annual pilgrimages to the grave in adding stones to a memorial cairn? Likely, yes. There is precedent for this. In June 1703 government officials from the colonies of New Hampshire and Massachusetts met with a Native American delegation at Casco Bay in Maine to discuss a peace treaty. Capt. Samuel Penhallow, an eyewitness wrote, . “as a testimony [of peace] thereof, they presented him [Gov. Dudley] a belt of wampum, and invited him [Gov. Dudley] to the two pillars of stones [stone heaps], which at a former treaty were erected, and called by the significant name of the Two Brothers; unto which both parties went and added a greater number of stones.” In turn the Native Americans signed the colonists’ paper treaty. Both cultures respected and participated in the other’s customs for formalizing the peace agreement.

The late 1700s festivities in Nova Scotia focused completely on St. Aspinquid. The other three Mi’kmaq leaders murdered were largely forgotten. Throughout the numerous accounts one factor has prevailed, only St. Aspinquid was acknowledged. That has lead people to assume he was the only person buried on the mountain. In which case, everyone has looked for a single grave.

In 2017, the authors investigated a large cairn and what appeared to be graves nearby reported to them by an anonymous researcher. We found four “graves” which were over a quarter mile from the nearest historic house foundation. This was odd because most family cemeteries are close to the house. James, co-author, began to question if we had re-located St. Aspinquid’s grave along with the graves of his three comrades. We also wondered about the significance of the old cairn. The 1600s memorial cairn concept fit.

The large cairn and graves seem to be the same ones mentioned in the 1857 reporter’s account although there is some discrepancy in the details. The Thimbleberry cairn was said to be twelve feet high. It may have been confused with the 1847 USGS survey cairn on the summit. The geological survey report states the summit cairn was fifteen feet high by eight feet square. A circa 1920 photograph with a ranger standing on top shows the cairn was approximately twelve feet high by eight feet square. It likely settled or stones were displaced and rolled down the sides due to people climbing on it like the ranger. The survey cairn was eight feet per side that is much shorter than the “rod” (16 ½ feet) stated in the Thimbleberry story. The summit cairn lacked a grave next to it, whereas, the old cairn on the lower slope has graves beside it. (Further, the reporter noted that the graves were “eastward of the monument” which is consistent with the layout of the graves which are east of the large cairn.) There is a strong possibly there were two large cairns on the mountain although it was not stated in the newspaper article. The reporter lost his notebook and had to write his article from memory which may account for the odd size of the cairn in the story. The cairn’s size does not match either the old cairn (26’ W x 36’ L x 5’ H) next to the graves or the new USGS summit cairn. It appears to be a composite of the two cairns.

The reporter who recorded the Thimbleberry story, described his descent down the mountain thus, “On we went, down and down and across; here over a log, there down a ravine, and here across a beautiful brook …” This describes the descent down the mountain to the now forested “open plain” with the cairn and graves. (The authors retraced the approximate route taken in 1857). It shows the cairn and grave[s] were on the slope of the mountain. Which in turn, is in agreement with the Bureau of American Ethnology’s statement, “He is said to be buried on the slope of Mt. Agamenticus.”

By 1857, the cairn and four graves already had some antiquity to them. The tour guide made up a fictitious story about the them. Although intended to entertain tourists, it was apparently also meant to cover a gap in the guide’s local knowledge.

Is this a family cemetery? A story in The Wild Artist in Boston dated 1888 gave the following, “They bade good-by to the lonely homestead. They saw the family burial ground, beside the road near the house.” This is an important piece of information because it says the house and family cemetery were near each other and next to the road. The four “graves” in the woods are over a quarter mile away from the house.

The four elongated mounds marked with head and foot stones are adult length, and neatly placed side be side (parallel to each other) spaced close together. The arrangement indicates the burial mounds (real or pseudo) were created at the same time. Four is the same number of Mi’kmaq killed at the fort therefore whoever created the burial mounds knew about the deaths. The head and footstones are period correct for the 1600s and 1700s. They appear to be four adult graves but are they a deception or purely representative of graves?

What about the 1857 local tour guide who told the Thimbleberry story? Did he use a field clearing stone pile and add a burial? Had he concocted a story about an old field clearing pile he would have only created one burial mound for Thimbleberry, not four.

After consulting with an historic burials expert, the authors learned that the mounds over the graves were out-of-character for a real burial. There should not have been a mound over each grave. The expert suggested these were memorials (pseudo graves) rather than real graves. This actually made sense. Both colonial records and Mi’kmaq oral history are silent on what happened to the bodies of the four murdered men.

Conclusion

This essay began by proposing the question “Is there any factual truth behind the legend?” It concludes by answering that question in the affirmative. St. Aspinquid was a respected Mi’kmaq tribal leader and diplomat, who along with tribal leaders Edgermett, Wipenen and Peminuit were treacherously murdered during a peace conference in 1696. In the ensuing centuries, St. Aspinquid’s name was elevated to a place of honor and his comrades sadly forgotten. The layers of Euro-American mythology surrounding the memorial have obscured his real story and caused many to doubt he ever existed.

The colonial historical records and Mi’kmaq oral tradition confirm he was a real person whose service to his people was tragically cut short. The discovery of a large cairn with four pseudo graves on the slope of Mt. Agamenticus raised the possibility that behind the legend was a fundamental truth, St. Aspinquid and the other three Mi’kmaq really were buried on the mountain at an unknown location. Collectively all the lines of evidence (oral histories, historical accounts and physical remains) points to the fact this is the original pilgrimage site and memorial cairn but not burial as it contains pseudo graves.

The investigation of this story began before the current social injustice movement emerged on the national stage in 2020. This is a 334 year old social injustice story which still needs to be addressed. By bringing out the real story behind the layers of Euro-American mythology, we can begin the process of restoring respect for St. Aspinquid, Edgermett, Wipenen and Peminuit and the Mi’kmaq and Penobscot Nations. The first step is by recognizing and acknowledging the real history, memorial “graves” and memorial cairn that exist behind the legend. By presenting this essay, the authors seek to take the first tentative step towards that goal.

Appendix A - Ceremonial Stone Landscape (CSL)

The term Ceremonial Stone Landscape (CSL) was introduced by the United South and Eastern Tribes, Inc. (USET) to identity and acknowledge the use of stone for ceremonial purposes by American Indians in United States. CSLs are made up of stone cairns, stone enclosures, stone niches, stone chambers, standing stone alignments, ceremonial stone walls and stone effigies.

The oral histories of the USET member tribes are independently supported by early colonial accounts by missionaries and others who witnessed American Indians actively using ceremonial stone cairns. They are also backed by archaeological evidence. James Mavor and Bryon Dix, who wrote the book Manitou: The Sacred Landscape of New England’s Native Civilization, conducted an excavation in 1983 on a stone cairn before it was prohibited. They uncovered two large deposits of charcoal radio-carbon dated to 790 and 875 B.P. (1160 A.D. & 1075 A.D.). In addition, 120 pieces of red ochre were found at the base of the cairn. Red ochre is well documented as being used ceremonially by American Indians. The combined data proved the cairn was built by American Indians. The cairn was one of a group of one hundred and ten cairns.

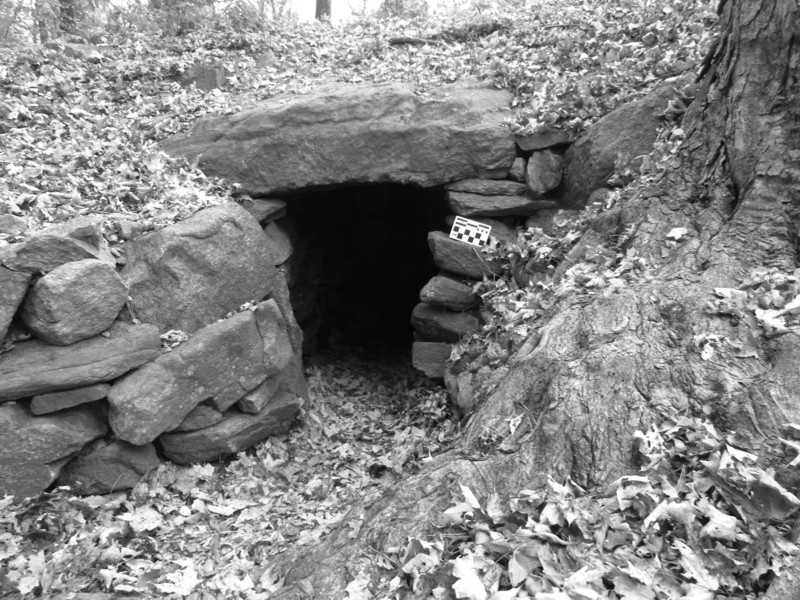

Stone chambers have also been dated prior to Euro-American settlement. A large beehive stone chamber in Upton, Massachusetts was dated using optically stimulating luminescence (OSL). (Figure 6) It returned a date range of from 1625 A.D. to 1350 A.D. This dates the structure prior to Euro-American settlement of the town.

On the Manitou Hassannash Preserve in Hopkinton, Rhode Island a rocky hill is inundated with over a thousand stone cairns and other ceremonial structures including niches, enclosures, and two serpent effigies. One ceremonial structure stands out for its use of symbolism. The stone cairn shown in figure 7 has three triangular stones carefully placed against it. Also from this same CSL is a split stone cairn shown in figure 8. In the American Indian anthropological literature splits in rocks are associated with portals to the spirit world through which humans and spirits could travel through and communicate with each other during ceremonies.

Euro-Americans in northeastern United States made extensive use of stone as a building material for stone walls, animal paddocks, building foundations, root cellars and boundary markers. Furthermore, on some farms, stones removed from crop and hay fields were placed in field clearing piles. One of the fundamental challenges today is how to distinguish an American Indian ceremonial cairn from a farmer’s field clearing pile, a ceremonial stone chamber from a root cellar, and so forth. The situation is complicated by the fact that some American Indian during the historic period adopted Euro-American farming techniques, housing and clothing while still continuing to practice traditional ceremonies. The authors of this essay, a mother and son research team, have developed a classification system for documenting stone structures and criteria for distinguishing utilitarian from ceremonial stone structures. This is a relatively new field of study.

|

Figure 6 – Large beehive stone chamber in Upton, Massachusetts date to 1625 A.D. to 1350 A.D. This dates the structure prior to Euro-American settlement of the town.

Figure 7 – Mound on ground cairn with three symbolic triangles slabs (Hopkinton, RI)

Figure 8 – Split stone cairn with stone offerings placed in split (Hopkinton, RI)